Commonplace 33 George & The Story He Did Write. PART TWO: The Diaries Version.

In Commonplace 31, I gave a fictional version of Marianne aka Nell's death. In Commonplace 32, I covered George's account based on his letter to Algernon dated March 1st 1888.

Now, let's look at George's version, taken from the Diaries.

The Diary entry background detail: George was on holiday in Eastbourne, joined briefly by Morley Roberts - Roberts plays fast and loose as usual with the facts in his account of this in 'Henry Maitland', but George was alone when he returned to his seaside lodgings to find the telegram: 'Mrs Gissing is dead. Come at once.'

We don't know who sent the telegram - we assume it was the landlady, Mrs Sherlock (I tend to think it was) on finding his address in Marianne's effects. If he was still paying Marianne/Nell directly himself by postal order (as he states in the Letters Vol. Two) and not making use of a solicitor, unless he paid her in cash face-to-face (which he might have done), then George will have been sending her letters every week. There is no reason to suggest these envelopes contained just the PO - there could have been friendly chat to which Marianne replied in letter form. I have always thought he stayed in touch with Marianne because he liked to have female acolytes and Marianne no doubt worshipped the ground he stood on. Paying her directly indicates a significant level of contact with Marianne largely overlooked (ie ignored) by biographers. George kept many valued friendships alive via letters, so writing to Marianne - and receiving her replies - right up to the time of her death, is not what many wish to consider. It would be a way of managing their relationship without either party totally losing out on whatever tenderness had brought them together but minus the need to address realities. We know she often made small needlework items for George and his brothers - and there is no reason to think this stopped when she was living alone - especially as she was beholding to him for her income and would want to celebrate xmas and his birthday.

Would it have come as a shock to him to learn she had been unwell? I doubt it. Lifelong chronic ill-health could only be expected to worsen. This might indicate George was fully aware of just how much her health had declined; though perhaps he didn't realise just how ill she was. And, if Marianne had no time to alert him to the sudden health crisis that claimed her he would be none the wiser about her perilous situation while he took the sea air on the south coast, buying tobacco from the too young Miss Curtis (thirteen years too young but living in a nice house in Eastbourne), aided and abetted for a while by Morley Roberts

Putting his address on the envelope would guarantee the envelope be returned if for some reason it was undelivered. As George makes no mention of uncashed money orders in the list he gives of her effects it suggests these were being regularly cashed by someone. There was a Post Office Receiving House round the corner from Lucretia Street at 151 Waterloo Road, mentioned in the Kelly's of 1859, so this might have been the place Marianne went to cash the orders. There is still a post office on the same site, though nowadays it's a modern parcel office building. Here it is: Weirdly, almost opposite this building both now and in Marianne's day is Holmes Terrace. Mrs Sherlock? Holmes Terrace? A Study in Scarlet (the first Sherlock Holmes outing) was published in 1888... A coincidence? Or is Mrs Sherlock a character in a fiction?

George's account from the Diary:

Thursd March 1. At 8.30 Roberts and I started for Lambeth. I felt an uncertainty about the truth of the telegram, and Roberts offered to go alone to 16, Lucretia Street, Lower Marsh, to make inquiries. I waited for him, walking up and down by Waterloo Station. He came back and told me that she was indeed dead. Thereupon we both went to the house: a wretched, wretched place. The name of the landlady, Sherlock. She told us that M H G died at about 9.30 yesterday morning, the last struggle beginning at 6 o'clock. They found my Eastbourne address in a drawer. I went upstairs to see the body; then Roberts accompanied me to the doctor who had been called in, name: McCarthy. Westminster Bridge Road. He gave us a certificate. Immediate cause of death, acute laryngitis. Roberts took his leave, and I returned to the house. Then a married daughter of Mrs Sherlock went with me to see the undertaker, of whom a coffin had already been ordered, - a man called Stevens, whom we found in a small beer-shop which he keeps, 99 Princes Rd, Lambeth. Arranged for a plain burial which is to cost 6 guineas. Leaving him, we went to the Registry Office, Lambeth Square, and registered the death. Thence to Lucretia Street again, where I arranged with the Sherlocks that they should attend the funeral. I am to give them £3 to buy mourning and pay their trouble and various expenses of late. After discussing these things, I went up to her room, to collect the things as I desired to take away. In Commonplace 31, I gave a fictional version of Marianne aka Nell's death. In Commonplace 32, I covered George's account based on his letter to Algernon dated March 1st 1888.

Now, let's look at George's version, taken from the Diaries.

The Diary entry background detail: George was on holiday in Eastbourne, joined briefly by Morley Roberts - Roberts plays fast and loose as usual with the facts in his account of this in 'Henry Maitland', but George was alone when he returned to his seaside lodgings to find the telegram: 'Mrs Gissing is dead. Come at once.'

We don't know who sent the telegram - we assume it was the landlady, Mrs Sherlock (I tend to think it was) on finding his address in Marianne's effects. If he was still paying Marianne/Nell directly himself by postal order (as he states in the Letters Vol. Two) and not making use of a solicitor, unless he paid her in cash face-to-face (which he might have done), then George will have been sending her letters every week. There is no reason to suggest these envelopes contained just the PO - there could have been friendly chat to which Marianne replied in letter form. I have always thought he stayed in touch with Marianne because he liked to have female acolytes and Marianne no doubt worshipped the ground he stood on. Paying her directly indicates a significant level of contact with Marianne largely overlooked (ie ignored) by biographers. George kept many valued friendships alive via letters, so writing to Marianne - and receiving her replies - right up to the time of her death, is not what many wish to consider. It would be a way of managing their relationship without either party totally losing out on whatever tenderness had brought them together but minus the need to address realities. We know she often made small needlework items for George and his brothers - and there is no reason to think this stopped when she was living alone - especially as she was beholding to him for her income and would want to celebrate xmas and his birthday.

Would it have come as a shock to him to learn she had been unwell? I doubt it. Lifelong chronic ill-health could only be expected to worsen. This might indicate George was fully aware of just how much her health had declined; though perhaps he didn't realise just how ill she was. And, if Marianne had no time to alert him to the sudden health crisis that claimed her he would be none the wiser about her perilous situation while he took the sea air on the south coast, buying tobacco from the too young Miss Curtis (thirteen years too young but living in a nice house in Eastbourne), aided and abetted for a while by Morley Roberts

Putting his address on the envelope would guarantee the envelope be returned if for some reason it was undelivered. As George makes no mention of uncashed money orders in the list he gives of her effects it suggests these were being regularly cashed by someone. There was a Post Office Receiving House round the corner from Lucretia Street at 151 Waterloo Road, mentioned in the Kelly's of 1859, so this might have been the place Marianne went to cash the orders. There is still a post office on the same site, though nowadays it's a modern parcel office building. Here it is: Weirdly, almost opposite this building both now and in Marianne's day is Holmes Terrace. Mrs Sherlock? Holmes Terrace? A Study in Scarlet (the first Sherlock Holmes outing) was published in 1888... A coincidence? Or is Mrs Sherlock a character in a fiction?

George's account from the Diary:

Now, to state it plainly, I do not think this Diary entry was written on March 1st 1888. I think George wrote an account in a March 1st 1888 diary - just not this one. We know George destroyed his diaries and many letters. I believe at a time of his life when he knew his health was failing, he decided to rewrite various scenes from memory to better present himself to posterity, and possibly to save the feelings of Walter and Alfred. If not but to manage our perceptions of both himself and his first wife, why would George have destroyed everything pretty much up to her death, and yet kept this, the longest entry of the first few pages? Why mention it at all when other references to her were expunged? I think it was to sow the seeds of what is now mistaken for fact by most biographers (all biographers?), which is: that George Gissing was not a cruel and unfeeling, selfish egoist who abandoned his first wife; Marianne was responsible for her own demise; that it was a sordid demise, and George could do nothing about it - see how hard he tried! - but it was Fate, that cruel, inexorable destiny that snarls at us all from birth to the grave.

Now, the novel written immediately after Marianne's death was The Nether World, George's last and possibly best-loved working class novel. Gentle reader, do you recall Mad Jack? Like some chorus in a Greek tragedy, Jack tells it like it is - here is an extract that could have been lifted right out of the March 1st Diary:

'A deranged creature, Mad Jack, at one point exclaims, 'There is no escape for you. From poor you shall become poorer; the older you shall grow the lower you shall sink in want and misery; at the end, there is waiting for you, one and all, a death in abandonment and despair. This is Hell- Hell - Hell!''

Which came first? The Diary entry for March 1st - or this snippet from Workers? I believe the Diary version followed Mad Jack by ten years at least - the rewritten entry is George as Mad Jack making it clear Marianne was doomed - doomed - doomed! But, the key word here is 'abandonment'. Because that's what George did to Marianne - though some carry on pretending he didn't.

So, go with me on this. Let us look at the above Diary segment.

If this Diary entry is contemporaneous, why use 'MHG' instead of a first name or even 'my wife'? After all, he knew who she was, and didn't need her whole name for clarification in initials form. A simple Nell or Helen or N or H would have sufficed. In fact, he doesn't refer to Marianne by name at all on March 1st. He even refers to her as 'poor thing' and 'poor creature' - two rather unpleasant nouns that follow his dehumanizing trend. Not a person but a 'thing' or a 'creature'...

It reads as if he knows whoever reads it after his death - when literary fame finally arrives? - will require all the gruesome details if they are to do his bidding and write his account in their biographies and critical reviews. Why else would he make all those bits of information read like a forensic witness statement? It's as if he is concentrating on shoving everything in mistakenly believing that adding minute specific detail confers authenticity. Did he learn nothing from 'Crime and Punishment' - that too much detail is suspicious? It certainly makes it read cold and distant - twelve years distant, IMO!

Why does George say Morley Roberts left him to it? Was it to ensure he did not have to account for an eyewitness whose version might be at variance with his own? I imagine he discussed his literary legacy with Roberts - perhaps the latter promised to clear up any ambiguities (by writing an ambiguous biography in 'Henry Maitland' haha) and make the best fist of the available biographical information. Morley Roberts was an odd creature (a future post for this one), but he was loyal to George. Perhaps George underestimated the quantity of evidence amassed and then much later to become available to dedicated Gissing scholars and random devotees over the coming years.

|

I covered 'acute laryngitis' in the previous post - a perfectly understandable cause of death. Mrs Sherlock had already arranged for the coffin - thus depriving George of the opportunity to waste good money on a posh one. That would leave plenty of cash to pay Mrs Sherlock £3 for her mourning outfit and for her daughter's (a Mr Sherlock is not mentioned, but he could have existed), and to offset expenses for attending Marianne's funeral. There might also have been other lodgers in 16, Lucretia Street - we don't know. Is there evidence Mrs Sherlock spent the £3 on black outfits? George would never know as he did not stick around for the funeral. George had been deeply traumatized at his father's interment and he didn't attend Will's funeral, so we can deduce he found such ceremonies too distressing. There is no reason to think Marianne shared a pauper's grave as a pauper's grave was for a pauper - which, clearly, Mrs Gissing was not. Later in the Diary, George mentions the burial cost 6 guineas. He says he visited Mr Stevens (the man who supplied the coffin) personally; we can assume he got what he paid for. A basic funeral was a working class funeral; it might take one of the Bryant and May girls (about to strike later in that year) 25 weeks to earn enough to pay for it. link Let us hope Mrs Sherlock was an upright citizen in this, did the decent thing and gave Marianne a fine send off.

To continue...

'Let me describe this room. It was the first floor back; so small that the bed left little room to move. She took it unfurnished for 2/9d a week; the furniture she brought was: the bed, one chair, a chest of drawers, and a broken deal table. On some shelves were a few plates, cups, etc. Over the mantelpiece hung several pictures, which she had preserved from the old days. There were three engravings: a landscape, a piece of Landseer, and a Madonna of Raphael. There was a portrait of Byron, and one of Tennyson. There was a photograph of myself, taken 12 years ago, - to which the landlady tells me she attached special value, strangely enough. Then there were several cards with Biblical texts, and three cards such as are signed by those who 'take the pledge', - all bearing date during the last six months.

On the door hung a poor miserable dress and a worn out ulster; under the bed was a pair of boots. Linen, she had none; the very covering of the bed had gone save one sheet and one blanket. I found a number of pawn tickets, showing that she had pledged these things during the last summer, - when it was warm, poor creature! All the money she received went in drink; she used to spend my weekly 15/- the first day or two that she had it. Her associates were women of so low a kind that even Mrs Sherlock did not consider them respectable enough to visit her house.

I drew out the drawers. In one I found a little bit of butter and a crust of bread, - most pitiful sight my eyes ever looked upon. There was no other food anywhere. The other drawers contained a disorderly lot of papers: there I found all my letters, away back to the American time. In a cupboard were several heaps of dirty rags; at the bottom had been coals, but none were left. Lying about here and there were medicine bottles, and hospital prescriptions.'

Let us consider this part. Marianne's small back-bedroom in a pale blue (on the Charles Booth map; see Commonplace 32) area sounds simple and basic - a typical working class back-bedroom, but not quite what is sometimes referred to as a 'box' room. Even though smallish, it still contained a bed, deal table, chair and a chest of drawers. As poor people didn't own many clothes, there was no need for a wardrobe. She might have had a wash stand as the house would not have stretched to a bathroom. What else did a single woman need? Did Marianne cook and make tea on her fire or down in the house kitchen? George mentions her deal table was broken - it adds to the shabby feel of the place, handy if you want to describe somewhere awful. He mentions the pictures - a photo of himself taken in 1876 ,'to which she attached special value strangely enough'. Was this phrase designed to make it obvious to us that she had no bad feelings toward him? I'm not suggesting she did - in fact, I believe both were much closer, emotionally, than is generally allowed for, and that their affection for each other endured. up to the end. It seems to be a ploy to make us believe he had always treated her well and she thought fondly of him, and she had no complaints. She did always have fond feelings for him, but I'm not sure he can lay claim to the other things.

Let us consider this part. Marianne's small back-bedroom in a pale blue (on the Charles Booth map; see Commonplace 32) area sounds simple and basic - a typical working class back-bedroom, but not quite what is sometimes referred to as a 'box' room. Even though smallish, it still contained a bed, deal table, chair and a chest of drawers. As poor people didn't own many clothes, there was no need for a wardrobe. She might have had a wash stand as the house would not have stretched to a bathroom. What else did a single woman need? Did Marianne cook and make tea on her fire or down in the house kitchen? George mentions her deal table was broken - it adds to the shabby feel of the place, handy if you want to describe somewhere awful. He mentions the pictures - a photo of himself taken in 1876 ,'to which she attached special value strangely enough'. Was this phrase designed to make it obvious to us that she had no bad feelings toward him? I'm not suggesting she did - in fact, I believe both were much closer, emotionally, than is generally allowed for, and that their affection for each other endured. up to the end. It seems to be a ploy to make us believe he had always treated her well and she thought fondly of him, and she had no complaints. She did always have fond feelings for him, but I'm not sure he can lay claim to the other things.The Biblical texts and the pledges - I suggest in my fictional version (Commonplace 31) that these were the result of Marianne attending a Christian-based Temperance group for more or less social reasons. I believe these pledges are taken by biographers exactly as George intended when he dropped them into his account - as evidence Marianne drank to excess. I disagree with this interpretation. In fact, signing the pledge was a typical thing for working class women to do - my old mother 'signed the pledge' in around 1934, when she was about 14. Pledge-signing (she told me) was a common feature of Sunday School attendance, often aimed at young women who were obviously vulnerable to being plied with alcohol and seduced by opportunistic youths. By signing, you demonstrated you were mindful of the risks of drink - hence the pledge card that you could flash at any predators. Girls were encouraged to sign up. Temperance was a sophisticated and holistic enterprise. It offered social gatherings, nourishing food, social housing, education, and free health advice and care. It was particularly popular with young people as it offered the chance to meet with persons of the opposite sex in safety because the boys had signed the pledge, too, and all were being monitored for propriety as much as sobriety by the Temperance staff. What the social side did was effectively provide 'pubs with no beer', a concept now rolled out in the UK by the NHS. Marianne could well have signed these pledges to gain access to a world of socialising and comfort she could not otherwise afford. It is lazy and unfair to limit this, as some do, to proof of drunkenness or alcoholism. In an age where there were huge levels of deprivation, the charitable sector plugged the gaps and often spearheaded the drive to social reform, but they were wise enough to know you couldn't ignore the needs people have for human interaction and the benefits of social attachment groups. Good food, pleasant company, music and warmth were free if you signed, and brought you a group who cared about you and your wellbeing, and demonstrated this in practical ways. The activities also catered for children and parents, so it was a microcosm for modelling good family values - a bit of an obsession in the nineteenth century.

-painting-artwork-print.jpg) George mention these pledges were all dated within the past 6 months - I suspect to reinforce the notion Marianne was a heavy drinker immediately before her death. Signing the pledge to gain access to hot food and warmth, company and free or cheap medicine makes common sense. We know Eduard Bertz was, for a while, a member of the Blue Ribbon Army - for which he would have had to 'sign the pledge'. Does that mean he was an alcoholic?

George mention these pledges were all dated within the past 6 months - I suspect to reinforce the notion Marianne was a heavy drinker immediately before her death. Signing the pledge to gain access to hot food and warmth, company and free or cheap medicine makes common sense. We know Eduard Bertz was, for a while, a member of the Blue Ribbon Army - for which he would have had to 'sign the pledge'. Does that mean he was an alcoholic?George mentions the small Art gallery Marianne owned. Not garish Herr Plitt-type cheapo adverts but classy stuff - portraits of poets and reproductions of classical paintings (and fashionable Landseer), all framed. Eminently pawn-able? If Marianne required funds for drink, why weren't these things in hock? He mentions the miserable clothes remaining - no doubt not pawn-worthy, but too good to throw away - possibly kept for recycling as patches. You hock what you don't really need and what will bring you the most money. As I suggest in my fictional account - how do we know Mrs Sherlock didn't sort through Marianne's possessions the minute she died and remove the things worth stealing? Clothes, bedding, knick-knacks, jewellery, coal, food, savings... we don't know if someone stripped Marianne's room bare of anything of value, thinking George would never notice or care - do we?

Pub landlords often provided a range of services. The March 1st version tells us Marianne's coffin was supplied by a Mr Stevens of a small beer-shop at 99, Princes Road. This was a far-ish hop from Lucretia Street, known as The Princes (sic) of Wales Beer House here . Princes Road where was where the new Lambeth workhouse (since demolished) was sited. see more here

George tells us 'all her money went in drink'. How could he possibly know this for sure? Did Mrs Sherlock really say it - as he claims? Did he have some other intelligence to go on? Did the landlady make it up? Or, did George use it to embellish the revised version? If he wants us to absolve him of his part in Marianne's dire situation, he needs us to think the worst of her. Doesn't it seem a little too convenient - a little too contrived - to be authentic? And, to make use of Mrs Sherlock to say it for him - a clever ploy to add a corroborating witness for his campaign to impugn Marianne's good name?

He adds: 'Her associates were women of so low a kind that even Mrs Sherlock did not consider them respectable enough to visit her house.' Now, we know George always disapproved of Marianne's friends. He did not like women, in general, to foregather together in the name of social intercourse, often remarking how disgusted he was at female 'gossip'. (Let us pass over the fact that he loved male gossip, and his letters are riddled with it. And that he adored Dr Johnson, Boswell and Mrs Piozzi. The very idea of a writer not liking gossip is frankly ridiculous!) But George had a dread of Marianne letting the cat out of the bag about the Owens days (and maybe even his treatment of her), leaving him open to bad press or even blackmail from her associates. Some of Marianne's friends once berated him for not looking after her properly - so any friend she made would be a threat to him. It was similar with Edith - he disapproved of her family and friendships she made with neighbours. Consider, if Mrs Sherlock really said it, might this not be to cover up her possible neglect of Marianne, her possible crimes of stealing, and to make sure George didn't ask difficult questions of Marianne's friends? Because their account of how she cared for Marianne might not have shown her as a paragon of virtue. If Mrs Sherlock was charging Marianne for nursing services rendered that were not delivered (and perhaps that is where all the 15/- went and why those prescriptions hadn't been used), then Marianne's friends might have had something to say to George about it. A working class woman telling a middle-class man his wife had been a drunk who consorted with immoral influences would have been deeply embarrassing to a husband. It would also guarantee he would hang around as little as possible, and not ask awkward questions about, for example, why his wife's room was so pathetically bereft of possessions. So, were Marianne's friends really beyond the pale? Isn't it far too coincidental to have the landlady make the exact same comment as George does in his letters - namely, that all Marianne's friends are vile?

It was strange that the room was full of medicine bottles and not gin bottles - if Marianne was supposed to be a drunkard. 'Lying about here and there were medicine bottles, and hospital prescriptions'. In fact, George makes no mention of any form of spirits or beer bottles in her room. One can assume then that there weren't any, because he would have mentioned it, don't you think? So, were there none sneaked away under the bed, or squirrelled away in the drawer under the dirty rags? He skates over the presence of medicine bottles and unused prescriptions, but the fact they were there does not indicate a life of dissipation, but a life of extreme ill-health. And, if the prescriptions were unused, an indication that she didn't have the money to pay for that vital treatment. Or that she couldn't get to the dispensary and her landlady couldn't be bothered to do it for her?

George made the most of this Dickensian scene, but he lacks the maestro's compassion and skill with sincerely meant heart-wrenching pathos. At the back of George's piece is a critical, coldly analytical self-serving sensibility. Charles Dickens would have made use of the relics of a life tragically cut short, to lead us to conclude we are all, at the bottom of it, the same under the skin. One is reminded of this piece written by Dickens about his favourite festival:

George made the most of this Dickensian scene, but he lacks the maestro's compassion and skill with sincerely meant heart-wrenching pathos. At the back of George's piece is a critical, coldly analytical self-serving sensibility. Charles Dickens would have made use of the relics of a life tragically cut short, to lead us to conclude we are all, at the bottom of it, the same under the skin. One is reminded of this piece written by Dickens about his favourite festival:

“I have always thought of Christmastime, when it has come

round...as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only

time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by

one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below

them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another

race of creatures bound on other journeys.”

Poor thing... Poor creature...

Of course, George's motives for describing in detail Marianne's death scene are not outward-going and for our moral and spiritual edification. They are to protect him from the charge that his neglect of his first wife was infamous and deeply unkind. And not manly or even mildly 'heroic'. Poor thing... Poor creature...

Gentle reader, read on...

'She lay on her bed covered with a sheet. I looked long, long at her face, but could not recognize it. It is more than three years, I think, since I saw her, and she had changed horribly. Her teeth all remained, white and perfect as formerly.

I took away very few things, just a little parcel: my letters, my portrait, her rent-book, a certificate of life assurance which had lapsed, a copy of my Father's "Margaret" which she had preserved, and a little workbox, the only thing that contained traces of womanly occupation."

George says it has been three years since he saw her - but had it been so long? If he was writing to her, sending the money regularly, might he not have passed her house to check she was still alive and his money orders were getting through to the right person? I am not suggesting they had a sexual relationship at this time - though I believe they had a marital relationship for years after they finally stopped co-habiting - however, it seems unrealistic to think he sent money out and hadn't bothered to follow it up. And, we have this: 'The other drawers contained a disorderly lot of papers; there I found all my letters, away back to the American time.' The phrase 'all my letters' suggests he had a regular correspondence with Marianne - and in these there must have been enough of worth for her to want to keep them and re-read them. Through all her ill-health and the direst of predicaments and situations, Marianne had clung to the days when George was a different person - maybe a kinder, better one. Considering he had abandoned her fully knowing how things would go for her, she still had love in her heart for him right to the end. And, he loved her, as much as he could ever love anyone.

I expect she had 'changed horribly' - half a lifetime of scrofula will do that to a face. George is careful not to qualify this with an description or explanation - he could have so easily remarked on the ailments, listing them and accrediting them with the appropriate nomenclature. He knew the disorders from which Marianne suffered and he knew these were all chronic and eventually, life-threatening. Again, he is vague about what ailed her because he wants the reader to carry on thinking Marianne was a dissipated drunk. However, a key phrase sheds light on her actual bodily situation: 'Her teeth all remained, white and perfect as formerly.' What can this tell us? Well, it suggests that Marianne was not a smoker, and that she never suffered from syphilis or alcoholism. The two ailments most often used to explain the poor state of her health both have devastating effects on the teeth. The acids in alcohol are enough to destroy the enamel and rot the gums, leading to tooth damage and loss. Syphilis itself very often is transmitted orally - and then frequently sets up home in the mucous linings of the mouth, where the gums perish, leading to tooth decay, and eventual bone loss. We have all seen those terrible anatomical illustrations where patients have horrendous loss of tissue to their mouths. Treatment in the days before antibiotics for any stage of syphilis was drastic - mercury was the standard. One way of checking the right amount was being used was the state of the patient's gums. The optimum dosage was achieved when the gums were bright red, but the teeth didn't wobble in their sockets. If they did wobble, the dosage was adjusted down until the gums recovered, then gradual increased doses of mercury was recommenced. One of the lasting side effects was tooth discolouration - teeth take on a blue-green tinge in the presence of mercury. It is plain, if Marianne's teeth were sound and white, it was because she did not have an illness that destroys teeth the way syphilis and alcoholism do. If you don't believe me click these:

info on mercury discolouration Slide 7

info on alcohol and teeth

info on syphilis and teeth

So, we have Marianne dead and George already feeling sorry for himself. You will know that online quote so often featured in GRG google searches: “Life, I fancy, would very often be insupportable, but for the luxury of self-compassion.” George has plenty of self-compassion with regard to Marianne's death. Much of the pity George wants us to feel when we read of it, is for him, not her.

He concludes this black day's entry:

'Came home to a bad, wretched night. In nothing am I to blame; I did my utmost; again and again I had her back to me. Fate was too strong. But as I stood beside that bed. I felt that my life henceforth had a firmer purpose. Henceforth, I never cease to bear testimony against the accursed social order that brings about things of this kind. I feel that she will help me more in her death than she balked me during her life. Poor, poor thing!

Here, we have one of the biggest lies George ever told: 'Henceforth, I never cease to bear testimony against the accursed social order that brings about things of this kind.'

Now, this is taken as a manifesto that informed the rest of George's writing career. Where is the evidence he lived up to this? When, exactly, did he 'never cease to bear witness' ? If this entry was written in 1888 - where is all this testimony? He had 15 more years to come up with it - if the entry was written in 1888. Most of his post-1888 work concerned the lower middle classes and above. The Nether World and some tepid short-stories were produced focusing on the lives of the poor, but the vast body of work after 1888 was not about 'the accursed social order' of the ordinary people like Marianne. Of course, by 1900, and with the literary legacy to manufacture, it might have been better to pass off many of his failings - and particularly the Owens debacle - as social science gone awry. His letter to Algernon of March 1st only says, 'Well, now it behoves me to get to work. I have a somewhat clearer task before me than hitherto, & one that will give me enough to do for many years'. this is not a manifesto for a personal philosophy: it is a manifesto about seizing the day - making enough money to live on in the full knowledge his phthisis would eventually kill him the way Marianne's TB had killed her.

Poor George - a sleepless night after seeing the dead body of the woman he once risked it all for and turned out into this bleak world, alone. Poor, poor George. Written down for posterity so suckers swallow it hook, line and sinker.

'In nothing am I to blame; I did my utmost; again and again I had her back to me. Fate was too strong.' Was it fate that did for Marianne? Or the wilful acts of an egoist carelessly abandoning a chronically sick dependent for purely selfish and amoral reasons? George wrote to Algernon on January 19th 1882, just over two years after marrying Marianne:

'I don't know that she is to be blamed for all this, seeing that, without a doubt, her mind is affected. Still, no-one is called upon to sacrifice everything to a weak-minded person's whims; & it is clear that this place cannot possibly be a home for her henceforth.'

George's biographers have very little time for Marianne. Pierre Coustillas, in the Heroic Life of George Gissing vol 1 sees it thus:

'Indeed, Gissing had nothing for which to blame himself. For several years he had given proof of rare patience, keeping Nell with him to the prejudice of his work and of his legitimate ambition. After they had parted he had paid her with the strictest punctuality her weekly alimony which she would hasten to squander in the vilest dramshops. Many in Gissing's place would have yielded to resentment or anger, but now that she was dead his sole reaction was one of pity...'

'... keeping Nell with him to the prejudice of his work and his legitimate ambition.' Only a man could write that.

'After they had parted he had paid her with the strictest punctuality her weekly alimony which she would hasten to squander in the vilest dramshops'... How on earth could Mr Coustillas know what Marianne spent her money on? Isn't biography meant to be an attempt at historic accuracy and objective truth?

PLEASE JOIN ME IN COMMONPLACE 34 WHERE WE LOOK AT THE NEXT PART OF GEORGE'S VERSION.

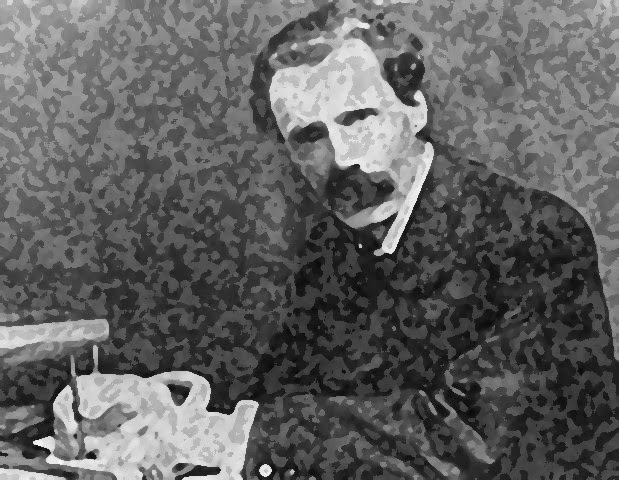

All these lovely photos are by the pioneering photographer Julia Margaret Cameron.

The Diaries

London and The Life of Literature in Late Victorian England:

The Diary of George Gissing Novelist. ed Pierre Coustillas. 1978; The Harvester Press.

http://www.angelpig.net/victorian/mourning.html for fascinating information on exactly what it says in the link title.

_-_Biblis_(1884).jpg)